Penry v. Lynaugh

Case Overview

CITATION

ARGUED ON

DECIDED ON

DECIDED BY

OVERRULED (IN PART) BY

492 U.S. 302

Jan. 11, 1989

Jun. 26, 1989

Atkins v. Virginia (2002)

Legal Issue

Is the death penalty a cruel and unusual punishment for a mentally retarded offender convicted of capital murder?

Holding

No, the execution of a mentally retarded offender is not a cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment.

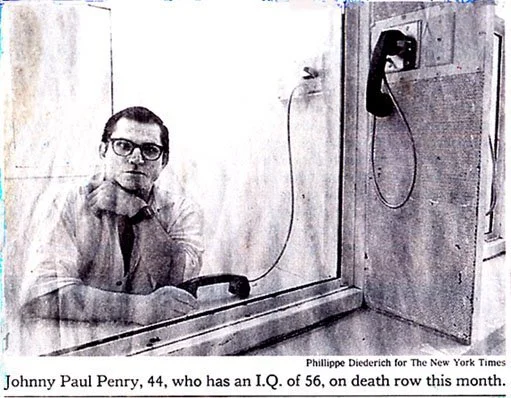

John Paul Penry, the appellant in the case | Credit: Phillippe Diederich, The New York Times

Background

In 1979, Pamela Carpenter was brutally raped, beaten, and stabbed with a pair of scissors in her home in Livingston, Texas. Before dying from her wounds, she provided a description of her assailant that led police to Johnny Paul Penry, who had recently been paroled for another rape conviction. Penry confessed to the crime and was charged with capital murder.

During the trial, extensive evidence regarding Penry’s mental health was presented. A clinical psychologist testified that Penry was mildly to moderately retarded with an IQ between 50 and 63 and the mental age of a six-and-a-half-year-old. Family members testified to severe abuse Penry suffered as a child, including being frequently beaten and locked in his room without a toilet. The State introduced rebuttal testimony from psychiatrists who, while acknowledging his limited mental ability, diagnosed him with an antisocial personality disorder and argued he was legally sane and aware of the difference between right and wrong.

The jury rejected Penry’s insanity defense and found him guilty of capital murder. Under Texas law at the time, the death penalty was determined by the jury’s answers to three “special issues”:

Whether the conduct was committed deliberately.

Whether the defendant would be a continuing threat to society.

Whether the killing was unreasonable in response to any provocation.

Penry’s attorneys objected to the jury instructions, arguing that these specific questions didn’t allow the jury to adequately consider his mental retardation and abuse history as mitigating reasons to spare his life. The trial court overruled the objections, and the jury answered yes to all three questions, resulting in a mandatory death sentence. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction and sentence, and the Supreme Court granted certiorari to determine if the jury instructions were unconstitutional and if the Eighth Amendment categorically prohibited the execution of a mentally retarded defendant.

5 - 4 decision for Lynaugh regarding the application of Teagues to capital cases and the merits of Penry’s 8th Amendment claim.

Stevens

Penry

Lynaugh

Brennan

Marshall

Scalia

Blackmun

White

Kennedy

Rehnquist

O’Connor

Unanimous decision for Penry regarding regarding the retroactivity and application of Teague.

Stevens

Penry

Lynaugh

Brennan

Marshall

Scalia

Blackmun

White

Kennedy

Rehnquist

O’Connor

5 - 4 decision for Penry regarding the “new rule” analysis under Teague and the merits of Penry’s jury instructions claim.

Stevens

Penry

Lynaugh

Brennan

Marshall

Scalia

Blackmun

White

Kennedy

Rehnquist

O’Connor

Opinion of the Court

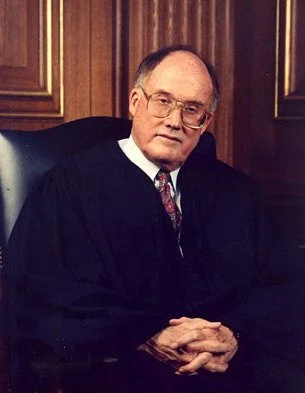

Writing for the Court in a splintered opinion, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor first addressed the issue of retroactivity under Teague v. Lane (1989), where the Court held that if the defendant is asking for a “new rule” of constitutional law, they generally can’t announce it or apply it to their case if their conviction is already final, unless it is a substantive rule or watershed procedural rule that’s “implicit in the concept of ordered liberty.” In this case, O’Connor found that the relief Penry sought regarding the special issues jury instructions didn’t constitute a “new rule” because it’s in line with the Court’s holdings that guarantee a defendant’s right to have mitigating evidence considered and given effect. While Penry was allowed to present evidence of his mental retardation and childhood abuse, the special issues instructions provided no opportunity for the jury to give mitigating effect to that evidence. O’Connor noted that Penry’s mental retardation could have logically forced a “yes” to the future dangerousness question, thereby turning his mitigating evidence into an aggravating factor. O’Connor stated that the jury should have been instructed that it could consider the mitigating evidence as a basis for a sentence less than death, and reversed Penry’s death sentence.

Regarding whether the Eighth Amendment categorically prohibits the execution of mentally retarded persons, the Court held that such a rule would be a “new rule” but would fall under the Teague exception for rules placing certain conduct or classes of people beyond the State’s power to punish. On the constitutional issue, however, O’Connor found that there was insufficient objective evidence of a national consensus against executing the mentally retarded. O’Connor pointed out that only one state and the federal government had explicitly banned the practice at that time, which did not constitute the overwhelming consensus required to deem the punishment "cruel and unusual." While the common law prohibited punishing “idiots”, which itself is distinct from the modern meaning of mentally retarded. Writing for herself and not the Court, Justice O'Connor further argued that mental retardation implies varying degrees of capability and that not all retarded individuals inevitably lack the moral culpability required for the death penalty, rejecting the use of “mental age” as a tool to draw the line for constitutionality.

Opinion by Justice Scalia

In a separate opinion joined by Chief Justice William Rehnquist, Justice Byron White, and Justice Anthony Kennedy, Justice Antonin Scalia concurred with the Court application of Teague and rejection of the categorical ban on executing the mentally retarded, but he strongly dissented from the Court’s holding regarding the jury instructions. Scalia pointed that the Court had previously upheld Texas’ sentencing law and argued that it allowed the jury to consider mitigating evidence sufficiently by determining whether the defendant acted deliberately or posed a future danger. Scalia argued that by requiring a special instruction that allows the jury to grant mercy based on generalized mitigation not relevant to the special issue questions, the Court was returning to the unguided, emotional discretion condemned in Furman v. Georgia (1972).

Additionally, while Scalia agreed that the Eighth Amendment doesn’t prohibit the execution of a mentally retarded offender, he rejected the proportionality analysis proposed by Justice O’Connor. Scalia ultimately concluded that analysis of the Eighth Amendment should be limited to whether a punishment is contrary to historical practices or current societal consensus, and that the Court has no authority to invalidate a punishment based on its own subjective view of what is proportionate.

Opinion by Justice Brennan

In a separate opinion joined by Justice Thurgood Marshall, Justice William Brennan concurred with the Court’s decision to remand the case for resentencing due to the faulty jury instructions but dissented from the Court’s holding that the Eighth Amendment permits the execution of the mentally retarded. Brennan also criticized the Court’s application of Teague to capital cases, arguing that it creates an arbitrary threshold that prevents federal courts from protecting constitutional rights based on the timing of a conviction. Defending a categorical ban, Brennan argued that the execution of mentally retarded defendants is always disproportionate to their culpability and serves no valid penal goal. Brennan contended that the clinical definition of mental retardation, which includes subaverage intellectual functioning and deficits in adaptive behavior, necessarily implies a reduced ability to control impulses, anticipate consequences, and engage in moral reasoning. Ultimately, Brennan concluded that such offenders can never possess the level of culpability required to justify the ultimate penalty of death, and that their execution contributes nothing to the goals of retribution or deterrence.

Opinion by Justice Stevens

In a separate opinion joined by Justice Harry Blackmun, Justice John Paul Stevens concurred in the Court’s decision to remand Penry’s case for resentencing but wrote separately to express his disagreement with the Court’s reliance on Teague and rejection of the categorical ban on executing the mentally retarded. Stevens pointed to the clinical evidence regarding the limited cognitive capacities of the mentally retarded, arguing that it shows that they don’t share the culpability of other adult offenders. Stevens ultimately concluded that in such cases, the imposition of the death penalty is excessive and therefore unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment’s protection from “cruel and unusual” punishment.