Plaut v. Spendthrift Farm, Inc.

Case Overview

CITATION

ARGUED ON

DECIDED ON

DECIDED BY

514 U.S. 211

Nov. 30, 1994

Apr. 18, 1994

Legal Issues

Does Congress have the authority to enact a law that retroactively requires federal courts to reopen a case in which they’ve issued final decision?

Holding

No, the Constitution’s separation of powers prevents Congress from enacting a law that retroactively requires federal courts to reopen a case in which they’ve issued a final decision.

Spendthrift Farm in Lexington, Kentucky | Credit: Erin Aiken

Background

In 1991, the Supreme Court ruled that actions brought under the securities laws, specifically §10(b) and Rule 10(b)(5), had to be brought within one year of discovering the facts that gave rise to the violation and three years of the actual violation. Congress then amended the law to allow cases that were filed before that decision to go forward if they could’ve been brought under the prior law. As a result, actions that had been dismissed under the Supreme Court’s prior ruling were revived.

Summary

7 - 2 decision for Spendthrift Farm

Plaut

Spendthrift Farm

O’Connor

Kennedy

Ginsburg

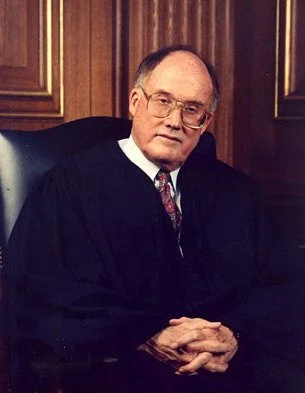

Rehnquist

Scalia

Stevens

Breyer

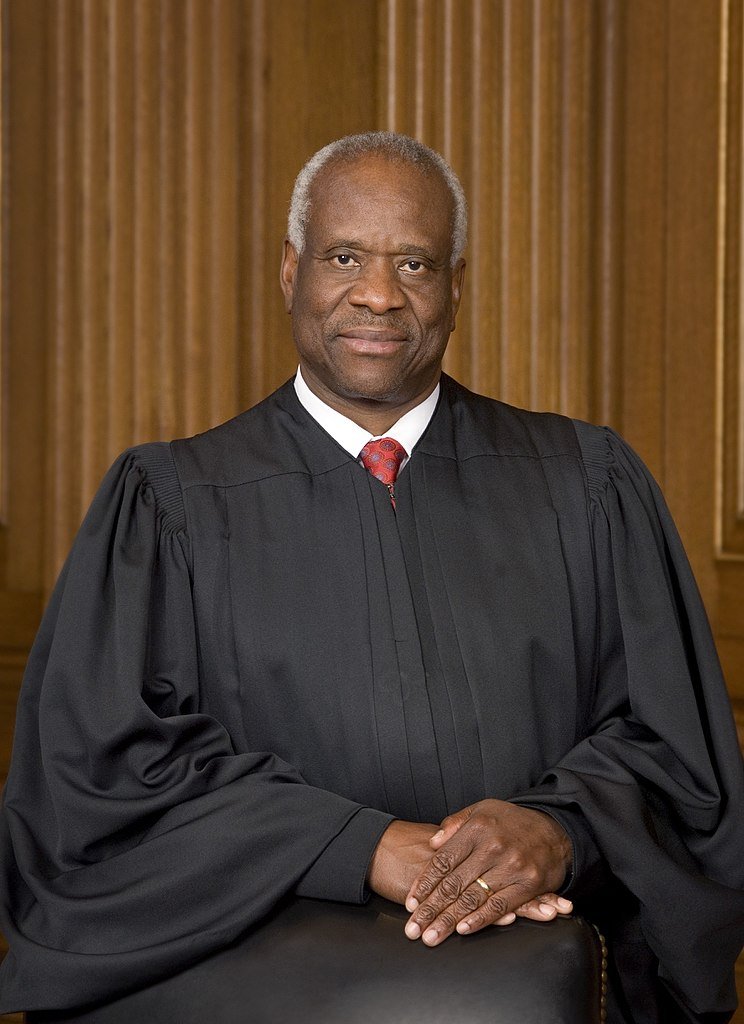

Thomas

Souter

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice Antonin Scalia held that §27A(b) of the Securities Exchange Act was unconstitutional because it required federal courts to reopen final judgments. Scalia began by establishing that Article III of the Constitution doesn't just give the Federal Judiciary the power to rule on cases, but also the power to decide them definitively. He argued that a fundamental part of the Constitution’s grant of judicial power is the ability to render dispositive judgments that are subject to review only by superior courts within the Article III hierarchy, rather than being subject to legislative revision.

Scalia explained that while Congress has the authority to “amend applicable law” and have those changes apply to cases still pending on appeal, it can’t use legislation to rescind a judgment once it has reached a final decision and the time for appeal has expired. Scalia distinguished between a “batch of unconnected courts” and a unified “judicial department” where the last court in the hierarchy provides the final word, emphasizing the importance of the Court’s constitutional framework for deciding issues.

Regarding the separation of powers, Scalia rejected the idea that the lack of individual favoritism or the presence of “good reasons” could save the statute. He emphasized that the principle of separation of powers is meant to power itself from interference, rather than just the prevention of corruption. Scalia argued that by commanding the courts to reopen final judgments, Congress had exceeded its authority and performed a role that the Constitution strictly denies it. Ultimately, the Court held that the Act violated the separation of powers by requiring federal courts to set aside final judgments entered before its enactment.