Massachusetts v. EPA

Case Overview

CITATION

ARGUED ON

DECIDED ON

DECIDED BY

549 U.S. 497

Nov. 29, 2006

Apr. 2, 2007

Legal Issues

Does the State of Massachusetts have standing under Article III to challenge the EPA’s refusal to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, and does the Clean Air Act authorize the EPA to regulate emissions from new motor vehicles as sought?

Holding

Yes, Massachusetts has standing to sue because it was entitled to “special solicitude” as a sovereign state, and the Clean Air Act authorizes the EPA to regulate greenhouse gases.

Protestors supporting Massachusetts outside the Supreme Court | Credit: NRDC

Background

In 1999, a group of private organizations filed a rulemaking petition asking the EPA to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from new motor vehicles under §7521(a)(1) of the Clean Air Act. The EPA requested public comment on the rulemaking petition in 2001. The EPA denied the petition in 2003, stating that it lacked authority under the Clean Air Act to regulate carbon dioxide and that even if it did have such authority, it was entitled to exercise its discretion to decline regulation as a matter of policy. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit ruled in favor of the EPA, and the Supreme Court granted certiorari.

5 - 4 decision for Massachusetts

Massachusetts

EPA

Kennedy

Stevens

Sotomayor

Kagan

Souter

Alito

Scalia

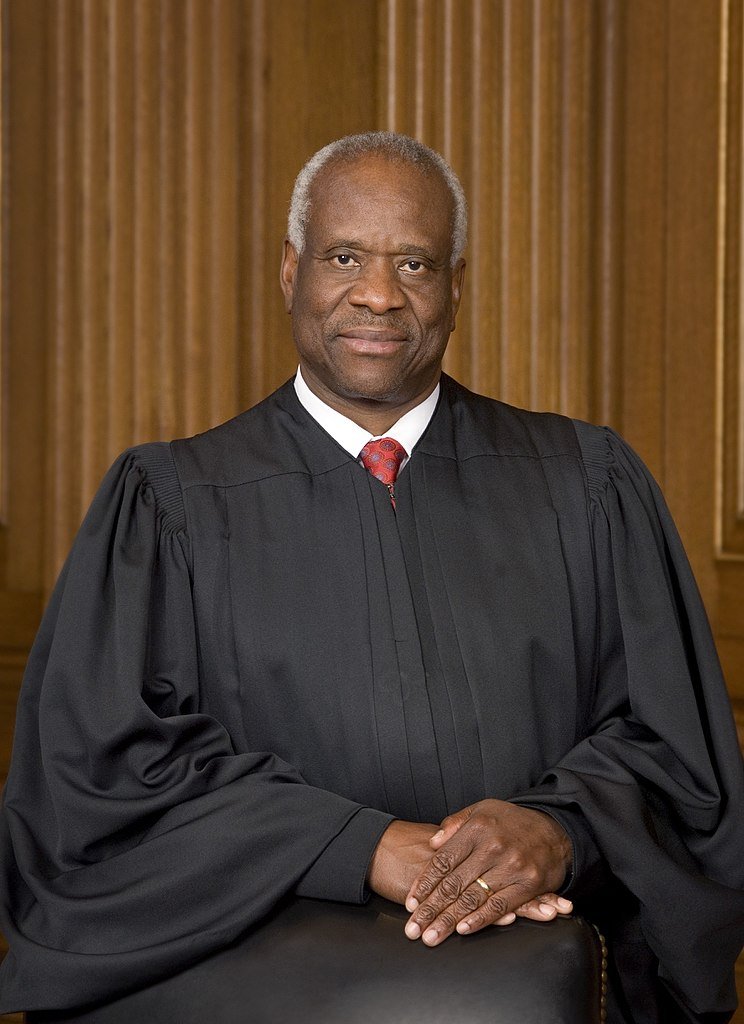

Thomas

Roberts

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice John Paul Stevens held that Massachusetts standing under Article III to challenge the EPA’s refusal to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. Stevens began by establishing that the “case or controversy” requirement of Article III is satisfied when a plaintiff demonstrates a personal stake in the outcome through an injury that is fairly traceable to the defendant and likely to be redressed by a ruling in their favor. However, Stevens emphasized that when a sovereign State is the party seeking protect its quasi-sovereign interests, such as greenhouse gas emissions, it’s entitled to “special solicitude” in the standing analysis.

Regarding the injury-in-fact, Stevens rejected the argument that the widespread nature of climate change harms precluded standing. Stevens agreed with Massachusetts argument that the rise in sea levels had already begun to “swallow” coastal land owned by Massachusetts, creating a risk of injury that was both actual and imminent. Stevens argued that the severity of this injury would only increase, with significant fractions of coastal property facing permanent loss through inundation. Stevens found that such an impact constituted a concrete and palpable injury to the Massachusetts’ interests.

Regarding causation and redressability, Stevens concluded that the EPA’s refusal to regulate emissions contributed to Massachusetts’ injuries. Stevens argued that while a single regulatory act might not reverse global warming entirely, a reduction in domestic emissions would “slow the pace of global emissions increases,” which would likely redress the harm to Massachusetts. Ultimately, the Court held that the petitioners met the standing requirements of Article III, permitting judicial review of the EPA’s action.

On the merits, Stevens rejected the EPA’s argument that it lacked statutory authority. Stevens pointed to the broad definition of “air pollutant” in the Act, which includes “any physical, chemical... substance or matter which is emitted into or otherwise enters the ambient air.” Stevens argued that the statute is unambiguous and that greenhouse gases “fit well within the Clean Air Act’s capacious definition.” Regarding the EPA’s argument that it was unwise to regulate even if it had the authority, Stevens found it to be "divorced from the statutory text.” He explained that while the statute conditions action on the formation of a “judgment”, that discretion is not “a roving license to ignore the statutory text.” Stevens noted that the EPA’s list of policy reasons, such as foreign policy concerns and a preference for voluntary programs “have nothing to do with whether greenhouse gas emissions contribute to climate change.” Stevens concluded that the EPA must “ground its reasons for action or inaction in the statute.” He emphasized that if “scientific uncertainty is so profound that it precludes EPA from making a reasoned judgment,” it must explicitly say so rather than relying on “impermissible considerations.” As a result, the Court reversed the lower court’s judgment and remanded the case, requiring the EPA to provide a reasoned explanation for its decision based on the statutory “endangerment” standard.

Dissenting Opinion by Chief Justice Roberts

In his dissenting opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts argued that the majority’s decision to grant “special solicitude” to Massachusetts lacked any basis in the Court’s jurisprudence and incorrectly relaxed the standard constitutional requirements for standing. Roberts explained that even if global warming was a “crisis” affecting humanity at large, it wouldn’t automatically create a “case or controversy” that could be heard in federal court.

Roberts also rejected the claim that Massachusetts suffered a concrete and particularized injury, explaining that a particularized harm must affect a plaintiff in a “personal and individual way” and “directly and tangibly” benefit them in a manner distinct from the public at large. Since global warming is potentially harmful to everyone, Roberts contended that the relief sought was inconsistent with the particularization requirement. Roberts further argued that the alleged loss of coastal land wasn't “actual or imminent” but was instead grounded in pure conjecture and a century-long timeline that failed the immediacy requirement.

Roberts also found that the petitioners couldn’t establish causation or redressability, noting that the burden is “substantially more difficult” when a party challenges the government’s failure to regulate a third party. Roberts pointed out that new domestic motor vehicles account for only a tiny fraction of global greenhouse gas emissions, making the link between the EPA's inaction and the loss of Massachusetts land far too speculative. On the issue of redressability, Roberts argued that any domestic reductions would likely be overwhelmed by the massive projected increases in emissions from developing nations like China and India. He characterized the belief that EPA regulation would prevent the loss of coastal land as “pure conjecture,” concluding that the Court’s relaxation of Article III requirements overstepped the judiciary’s constitutional boundaries.