Bowers v. Hardwick

Case Overview

CITATION

ARGUED ON

DECIDED ON

DECIDED BY

OVERRULED BY

478 U.S. 186

March 31, 1986

June 30, 1986

Lawrence v. Texas (2003)

Legal Issue

Does Georgia’s law prohibiting sodomy violate the Fourteenth Amendment?

Holding

No, Georgia’s law prohibiting does not violate the Fourteenth Amendment because sodomy is not a constitutionally protected right.

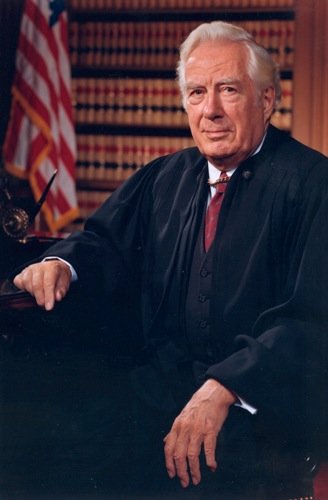

Michael Hardwick and his attorney | Credit: GSU Digital Collection

Background

In July of 1982, Michael Hardwick was cited for public drinking by Keith Torick, an officer with the Atlanta Police Department. Hardwick, however, missed his court date and Torick obtained a warrant for his arrest. In August of the same year, after the warrant had become invalid, Torick executed the warrant on Hardwick’s home. When Torick entered Hardwick’s bedroom, he observed Hardwick and another male engaging in consensual sex. Torick subsequently charged the pair for for engaging in consensual sexual conduct with another adult male, which violated Georgia’s statute criminalizing sodomy. After the initial hearing, the district attorney opted not to pursue since Torwick’s warrant was expired. Hardwick then filed suit in federal district court, challenging the constitutionality of the statute and claiming that it endangered his liberty. The district court dismissed the case, but the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit reversed and remanded, holding that the Georgia statute infringed on Hardwick’s fundamental rights to privacy, intimate association, and liberty under the Ninth and Fourteenth Amendments. The Supreme Court granted certiorari due to conflicting appellate decisions on similar statutes and to resolve the constitutional question at issue.

Summary

5 - 4 decision for Bowers

Bowers

Hardwick

Burger

Powell

Blackmun

O’Connor

Marshall

Rehnquist

Brennan

Stevens

White

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice Byron White ruled that the Constitution does not confer a fundamental right to engage in homosexual sodomy. The Court rejected the notion that Hardwick’s case was analogous to previous privacy cases decided by the Supreme Court, asserting that “[n]one of the fundamental rights announced in this Court’s prior cases involving family relationships, marriage, or procreation bear any resemblance to the right asserted in this case”. The Court pointed to historical evidence , noting that sodomy laws have “ancient roots,” and were criminalized under common law as well as by all thirteen original states at the time the Bill of Rights was ratified, and in nearly all states when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted. Justice White argued, “[a]gainst this background, to claim that a right to engage in such conduct is ‘deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition’ or ‘implicit in the concept of ordered liberty’ is, at best, facetious” .

Hardwick argued that the privacy of the home should afford constitutional protection. Justice White distinguished Hardwick’s case from the facts of Stanley v. Georgia (1969), which was anchored in the rights of the First Amendment. He explained, “[v]ictimless crimes, such as the possession and use of illegal drugs, do not escape the law where they are committed at home.” Justice White was also unpersuaded by the argument that laws based solely on morality are unconstitutional, stating that the law “is constantly based on notions of morality”. Ultimately, the Court concluded that there was insufficient reason to find that the substantive reach of the Due Process Clause should extend to cover consensual homosexual sodomy.

Concurring Opinion by Chief Justice Burger

In his concurring opinion, Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote separately to emphasize the moral and historical condemnation of homosexual sodomy. He described the prohibition as “firmly rooted in Judeao-Christian moral and ethical standards,” noting that it was a capital crime under Roman law and regarded as “a crime not fit to be named” under English common law. Chief Justice Burger concluded, stating that “[t]o hold that the act of homosexual sodomy is somehow protected as a fundamental right would be to cast aside millennia of moral teaching.”

Concurring Opinion by Justice Powell

In his concurring opinion, Justice Lewis Powell agreed with the majority that there is no fundamental right to homosexual sodomy under the Due Process Clause, but he wrote separately to note that the severity of punishment authorized by Georgia for a single act of consensual sodomy (1 to 20 years of incarceration) could raise serious Eighth Amendment concerns in the future. However, Powell explained that Hardwick had not been convicted nor raised the Eighth Amendment issue, so that question was not before the Court.

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Blackmun

In his dissenting opinion, Justice Harry Blackmun argued that the Court’s opinion misconstrued the case as about homosexual sodomy rather than the right to privacy, stating, “[t]his case is about ‘the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men,’ namely, ‘the right to be let alone’”. Justice Blackmun also criticized the majority’s reliance on tradition, arguing that “[i]t is revolting to have no better reason for a rule of law than that so it was laid down in the time of Henry IV.” Justice Blackmun also distinguished between laws protecting public sensibilities (prohibitions of public sex or drunkenness) and those policing private, consensual conduct. He stated, “The mere fact that intimate behavior may be punished when it takes place in public cannot dictate how States can regulate intimate behavior that occurs in intimate places.” Justice Blackmun concluded that laws criminalizing private, adult sexual conduct were unjustifiable and that the Court’s decision was offensive to personal liberty.

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Stevens

In his dissenting opinion, Justice John Paul Stevens emphasized that the Georgia statute applies to both heterosexual and homosexual conduct, and that the Court’s rationale and the law itself “applies equally to the prohibited conduct regardless of whether the parties who engage in it are married or unmarried, or are of the same or different sexes.” Justice Stevens argued that previous decisions reinforce privacy and intimate association as fundamental liberties and that history and tradition alone could not justify sodomy laws, referencing Loving v. Virginia (1967) as an example. Ultimately, Justice Stevens concluded that selective enforcement against homosexuals was indefensible under the Constitution and that the State had failed to provide any legitimate interest to justify its law.