Allen v. Wright

Case Overview

CITATION

ARGUED ON

DECIDED ON

DECIDED BY

468 U.S. 737

Feb. 29, 1984

July 3, 1984

Legal Issues

Did the Respondents have standing to sue in federal court based off an injury that did not effect them directly?

Holding

No, Article III of the Constitution requires plaintiffs in federal court to state a personal injury that is “distinct and palpable” and “fairly traceable” to the defendant’s alleged unlawful conduct, not an “abstract” injury.

Pastor W. Wayne Allen, founder of the Briarcrest Christian School | Credit: Briarcrest Christian School (1975)

Background

The IRS requires schools applying for tax-exempt status to show that they admit “students of any race to all the rights, privileges, programs, and activities generally accorded or made available to students at that school and that the school does not discriminate on the basis of race in administration of its educational policies, admissions policies, scholarship and loan programs, and athletic and other school-administered programs.” Failure to comply with the guidelines “ordinarily” resulted in revocation of the school’s tax-exempt status.

Respondents (Wright) were parents of black children in seven states where public schools were recently desegregated. In 1976, the Respondents filed a suit in the Federal District Court for D.C. against the Secretary of the Treasury and the Commissioner of the IRS, challenging the IRS’ guidelines and procedures and alleging while public schools in their communities were being desegregated, a number of racially segregated private schools were created or expanded. Their complaint identified 17 schools or school systems by name that receive tax exemptions either directly or through “umbrella” organizations that oversee them.

Regarding their injury, the Respondents alleged that the Government’s conduct:

Constitutes tangible federal financial aid and other support for racially segregated educational institutions.

Fosters and encourages institutions providing racially segregated educational opportunities, which interferes with the efforts of federal courts.

Summary

5 - 3 decision for Allen

Allen

Wright

White

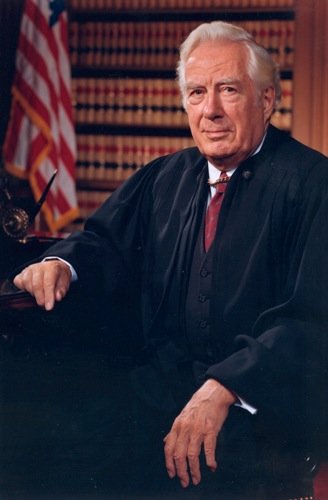

Burger

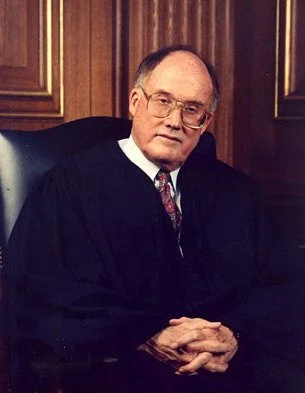

Rehnquist

O’Connor

Powell

Stevens

* Justice Marshall took no part in the consideration or decision of this case.

Brennan

Blackmun

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor held that the Respondents lacked standing to bring their suit in Federal Court. O’Connor began by establishing that the “case or controversy” requirement of Article III of the Constitution is a fundamental limit on federal judicial power that was designed to ensure that the judiciary doesn’t intrude upon the power Executive or Legislative branches.

O’Connor explained that to have standing in federal court, a plaintiff must allege a personal injury that’s “distinct and palpable” and “fairly traceable” to the defendant’s allegedly unlawful conduct, and it must be likely to be redressed by the requested relief. Such requirements prevent the courts from becoming a forum for generalized grievances about how the government is being run, which is the role of the political branches.

O’Connor rejected the Respondents’ first claim that the denigration suffered by black citizens when the government provides financial aid to discriminatory schools constituted a “stigmatic injury” that could provide standing. O’Connor explained that such a claim is only able to provide standing if the plaintiffs have personally been denied equal treatment by the institutions in question. Since the Respondents didn’t seek to enroll their children in the private schools, their injury was abstract and lacked the personal stake required by Article III. O’Connor noted that if standing were granted on this basis, any citizen could challenge any government action they found ideologically or morally offensive, which would turn the courts into monitors of the Executive Branch’s internal administrative policies.

Regarding the Respondent’s second claimed injury that the government’s actions impaired their children’s right to an integrated education, O’Connor found that it failed the causation and redressability prongs of the standing test. While O’Connor conceded that the Respondents established “causation in-fact” regarding their injury, they couldn’t show that their injury was “fairly traceable” to the alleged unlawful action since their claim relied on the independent and unpredictable decisions of third-party parents not party to the suit. On whether the alleged injury was likely to be redressed by the requested relief, O’Connor emphasized that it was purely speculative whether the withdrawal of tax-exempt status would actually lead to school integration.

She argued that allowing such a suit would force the judiciary to oversee the IRS’ enforcement of the law, which would violate the Executive Branch’s duty under Article II to “faithfully execute the laws.” Ultimately, the Court held that the Respondents lacked standing to bring the suit.

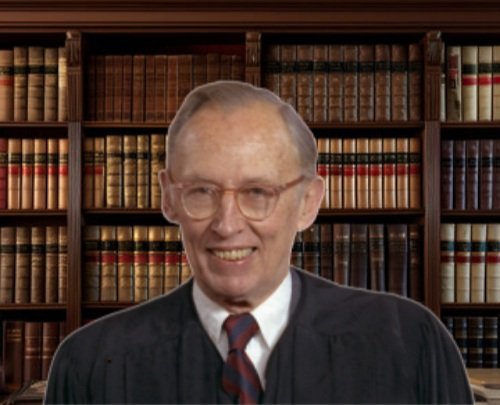

Dissenting Opinion by Justice Stevens

In his dissenting opinion, Justice John Paul Stevens strongly disagreed with the Court’s finding that the Respondents’ injury wasn’t “fairly traceable” to the IRS’ tax policies. Stevens began by arguing that the Respondents had clearly satisfied the Article III standing requirements since the government’s grant of tax exemptions to discriminatory schools essentially functioned as a subsidy for “white flight.” Since this subsidy directly contributed to the injury of public school segregation, the injury was “fairly traceable”.

Stevens argued that the tax-exempt status at question is legally indistinguishable from direct government subsidies, which function to encourage a certain activity. Thus, the withdrawal of that benefit would discourage the activity and promote desegregation. Stevens stated that by failing to recognize this link, the Court was allowing the government to remain a partner in unlawful discrimination. Stevens ultimately concluded that the Court’s ruling was less about Article III standing and more about to the underlying substantive claims of the lawsuit.