Weems v. United States

Case Overview

CITATION

ARGUED ON

DECIDED ON

DECIDED BY

217 U.S. 349

Nov. 30-Dec. 1, 1909

May 2, 1910

Legal Issues

Is a severe sentence of cadena temporal for the crime of falsifying a document a “cruel and unusual” punishment under the Eighth Amendment?

Holding

Yes, the Eighth Amendment prohibits punishments that are “cruel and unusual” in both degree of severity and proportion to the crime, and a sentence of cadena temporal for falsifying a document is cruel and unusual.

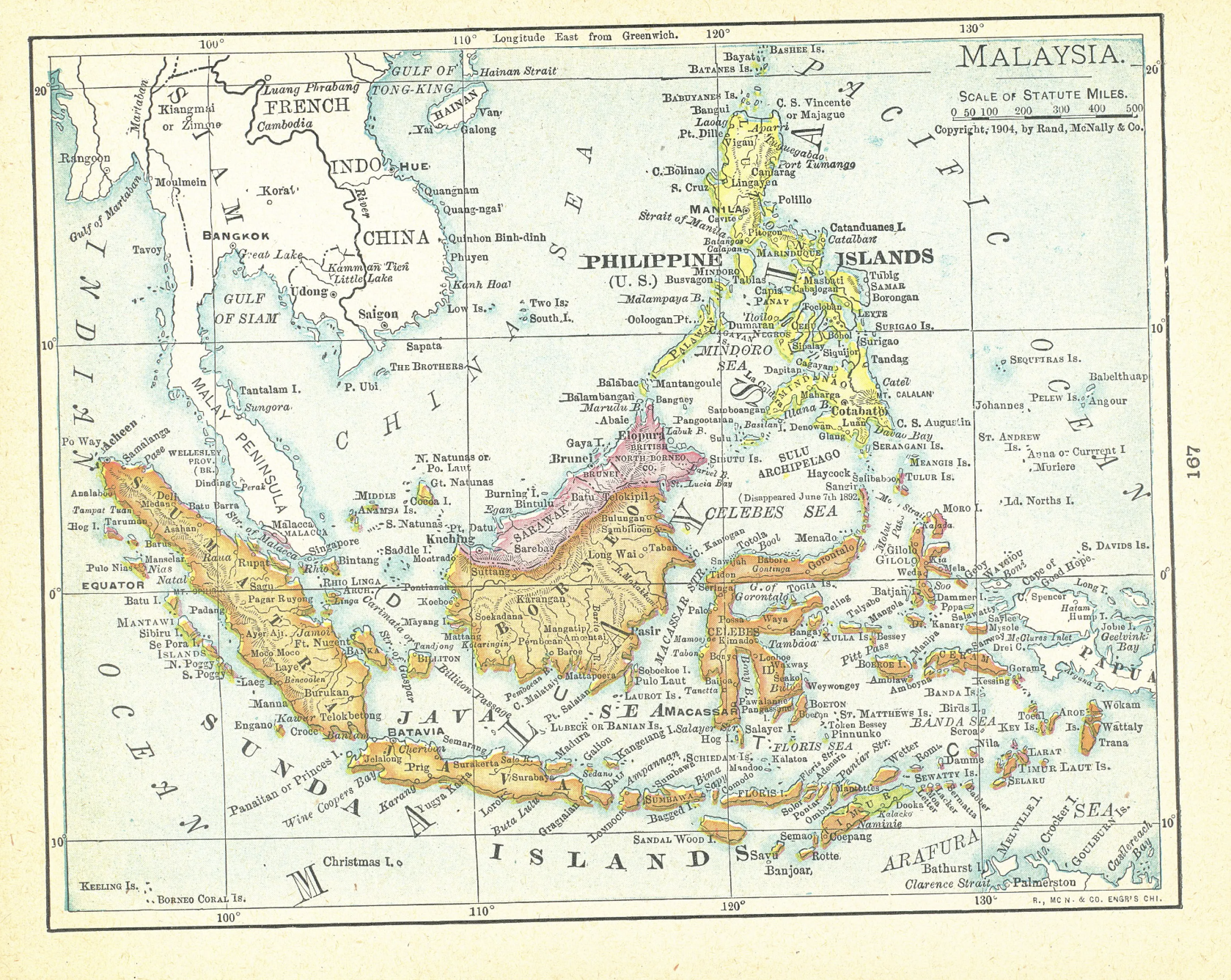

Vintage map page from a 1910 Dollar Atlas of the World | Credit: Green Basics

Background

In the early 1900s, Paul A. Weems served as a disbursing officer for the Bureau of Coast Guard and Transportation in the Philippines, which a U.S. territory at the time. In 1901, Weems was charged with “falsifying a public and official document” for the purpose of defrauding the government. Specifically, he was accused of making two false entries in a cash book totaling 616 Philippine pesos.

After being convicted in the Philippine courts, Weems was sentenced under the Spanish Penal Code to a penalty known as cadena temporal. This severe sentence included:

15 years of incarceration in a penal institution.

Hard and painful labor for the duration of the term.

Carrying a chain at the ankle, hanging from the wrist, at all times.

Civil interdiction, which deprived him of parental and marital authority and the right to manage his own property.

Perpetual absolute disqualification from holding public office or exercising political rights, such as voting, for life.

Surveillance by authorities for the remainder of his life after release.

Weems appealed his conviction to the Supreme Court of the Philippine Islands, which upheld the sentence. He then filed a writ of error to the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing that the punishment was “cruel and unusual” and violated the Eighth Amendment (or the nearly identical provision in the Philippine Bill of Rights). The U.S. Supreme Court granted certiorari to address for the first time whether a punishment was unconstitutional based on its excessive length and severity relative to the crime committed, rather than just the method of punishment itself.

4 - 2 decision for Weems

Harlan

Weems

U.S.

Day

McKenna

Holmes

Fuller

White

* Justices Moody and Lurton took no part in the consideration or decision of this case

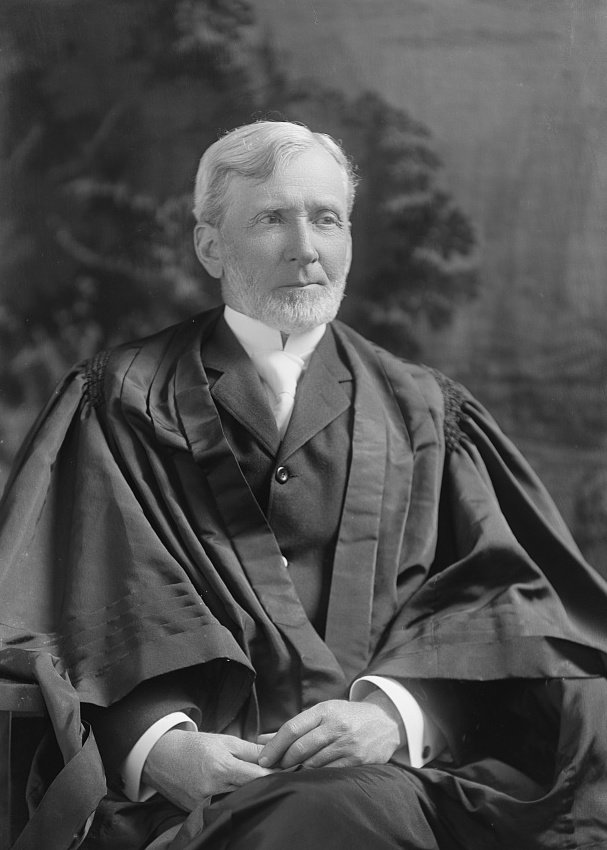

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice Joseph McKenna stated that the sentence of 15 years’ cadena temporal was a “cruel and unusual” punishment under the Eighth Amendment. McKenna emphasized that the Eighth Amendment is “progressive” and not limited to the specific barbarous acts known to the Founders. McKenna instead argued that the Eighth Amendment must be capable of wider application than just prohibiting the original punishments feared when it was written, especially as public opinion becomes “enlightened by humane justice.” McKenna also argued that the Eighth Amendment prohibits punishments that are greatly disproportioned to the offense, finding it “amazing” that a minor falsification of a public record carried a minimum penalty more severe than many homicides or violent crimes against the state.

McKenna concluded that the Eighth Amendment applies to both the degree and the kind of punishment. McKenna singled out the “accessories” of the sentence, such as being chained at the ankle and wrist, the loss of parental and property rights, and life-long surveillance, noting that these penalties “amaze those who have formed their conception of the relation of a state to even its offending citizens.” Since the “fault was in the law itself” rather than just the specific sentence, and no other law existed to punish the act, the Court ordered the judgment reversed and dismissed the proceedings.

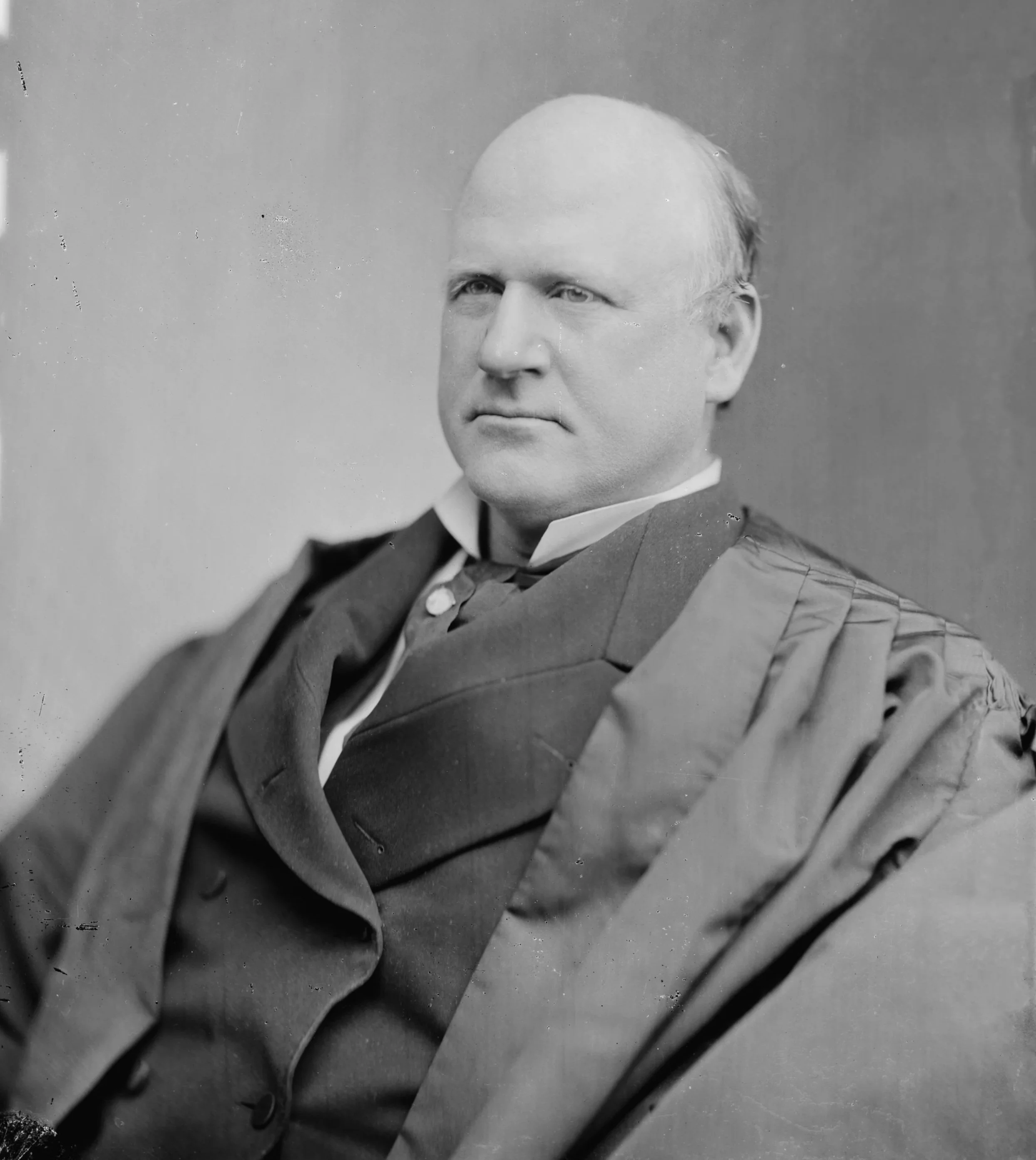

Dissenting Opinion by Justice White

In his dissenting opinion, Justice Edward Douglass White argued that the Eighth Amendment was intended only to prohibit inhumane and barbaric methods of bodily torture, such as those used by the Stuarts in England. White contended that the majority’s “progressive” interpretation incorrectly expanded the Eighth Amendment’s scope to include the mere length or severity of a sentence in proportion to the crime. Rather, White explained that the power to define crimes and determine the adequacy of punishments is a purely legislative function. By reviewing the proportionality of a sentence, White argued that the judiciary was unconstitutionally reviewing legislative discretion and disregarding the fundamental distinction between the branches of government.

White also argued that even if certain “accessory” punishments were deemed unconstitutional, they should be considered separable from the main term of imprisonment. White believed the Court should have at least upheld the legal portion of the sentence (the incarceration) rather than dismissing the entire proceeding. Ultimately, White concluded that since imprisonment at hard labor is a usual and authorized mode of punishment, the Court had no authority to interfere with the term of years prescribed by the legislature, regardless of whether the punishment seemed excessive compared to the offense.