Thompson v. Utah

Case Overview

CITATION

170 U.S. 343 (1898)

ARGUED ON

March 4, 7, 1898

DECIDED ON

April 25, 1898

DECIDED BY

Legal Issue

Does the Utah State Constitution’s requirement that juries in courts of general jurisdiction be composed of eight members violate the Sixth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution?

Holding

Yes, the Sixth Amendment provides a constitutional right to a 12-member jury in criminal trials.

A farmer stopped outside the local agricultural store in the Utah Territory in the early 1890s | Credit: Utah State Historical Society

Background

On March 2, 1895, Jack Moore stole a calf from his neighbor and was subsequently charged with grand larceny. The first trial was held when Utah was a Territory and, at the time, the territorial laws of Utah provided that juries be composed of 12 members of the community. Moore was found guilty, but he was soon after granted a new trial.

The second trial did not take place until after Utah became a state in 1896. In contrast to the territorial laws, the Constitution of the State of Utah proscribed an eight member jury for courts of general jurisdiction. As a result, Moore was tried before an eight member jury in his second trial. He was again found guilty, but he appealed the verdict and objected to the size of the jury. The trial court denied his appeal he was sentenced to three years in state prison. The conviction was confirmed by the Supreme Court of Utah, who held that a jury composed of eight members was consistent with the United States Constitution.

Summary

7 - 2 decision for Thompson

Thompson

Utah

Fuller

Brown

Gray

Shiras

White

Brewer

McKenna

Peckham

Harlan

Opinion of the Court

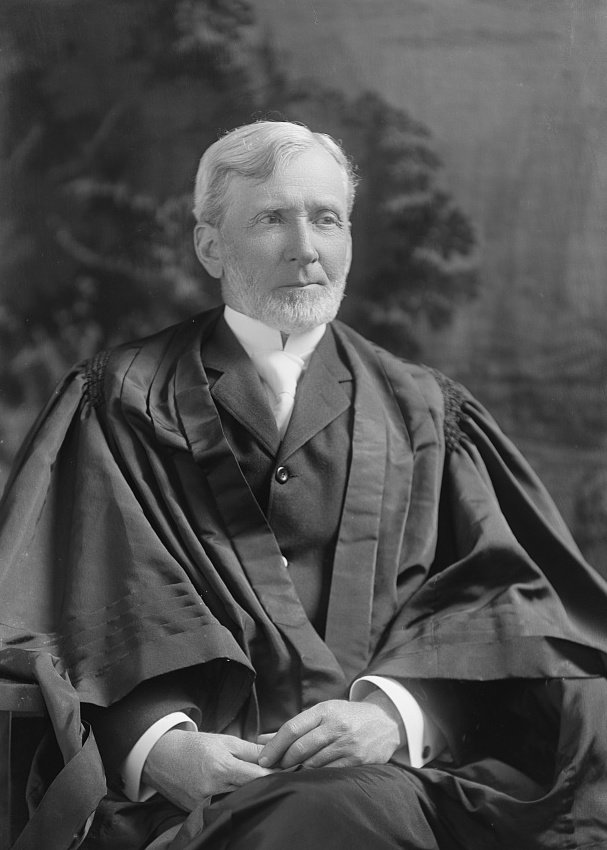

Writing for the Court, Justice John Harlan I held that the defendant, Thompson, was entitled to a trial by a jury of twelve persons under the Sixth Amendment of the United States Constitution. Harlan also argued that Utah’s state law that allowed for smaller juries in certain cases could not be applied to Thompson’s crime, which was committed when Utah was still a territory because it would be an unconstitutional ex post facto application of the law. He wrote, “[i]f, in respect to felonies committed in Utah while it was a Territory, it was competent for the State to prescribe a jury of eight persons, it could just as well have prescribed a jury of four or two, and, perhaps, have dispensed altogether with a jury, and provided for a trial before a single judge.”

Justice Harlan emphasized that the right to a trial by jury, as understood at the time of the adoption of the Constitution, meant a jury composed of twelve persons. This interpretation was based on historical practices dating back to England and the early American colonies, where a jury traditionally consisted of twelve members. Harlan argued that the Sixth Amendment's guarantee of a jury trial was meant to preserve this traditional jury size, which was fundamental to the Anglo-American system of justice. He explained, “[b]ut the wise men who framed the Constitution of the United States and the people who approved it were of opinion that life and liberty, when involved in criminal prosecutions, would not be adequately secured except through the unanimous verdict of twelve jurors. It was not for the State, in respect of a crime committed within its limits while it was a Territory, to dispense with that guarantee simply because its people had reached the conclusion that the truth could be as well ascertained, and the liberty of the accused be as well guarded, by eight as by twelve jurors in a criminal case.” The Court reversed Thompson's conviction, ruling that the use of an eight-person jury violated his constitutional rights and remanding the case for further proceedings in line with the Court’s opinion.

Justices Brewer and Peckham did not write a dissenting opinion.