Schenck v. United States

Case Overview

CITATION

249 U.S. 47 (1919)

ARGUED ON

January 9, 10, 1919

DECIDED ON

March 3, 1919

DECIDED BY

OVERRULED (IN PART) BY

Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969)

Legal Issue

Is right to free speech violated by a prohibition of speech that is critical to the United States’ war effort and the draft during war time?

Holding

No. Especially during wartime, the government has the right to regulate speech that may create a clear and present danger to national security.

Anti-war protesters at the US Capitol in April 1917 | Credit: The Library of Congress

Background

During World War I, Congress passed the Espionage Act of 1917, which stated that “whoever, in time of war, with intent that the same shall be communicated to the enemy, shall collect, record, publish or communicate, or attempt to elicit any information. . . which might be useful to the enemy, shall be punished by death or by imprisonment for not more than thirty years.”

Charles Schenck and Elizabeth Baer were arrested for distributing leaflets that compared the Unites States’ draft effort to slavery and argued it was thus was unconstitutional under the 13th Amendment. They were charged with conspiracy to violate the Espionage Act for attempting to undermine the United States Military’s recruitment and war efforts. Both were found guilty during their jury trials, but they appealed their convictions to the Supreme Court on the grounds that their right to free speech was violated.

Summary

Unanimous decision for the United States

Schenck

United States

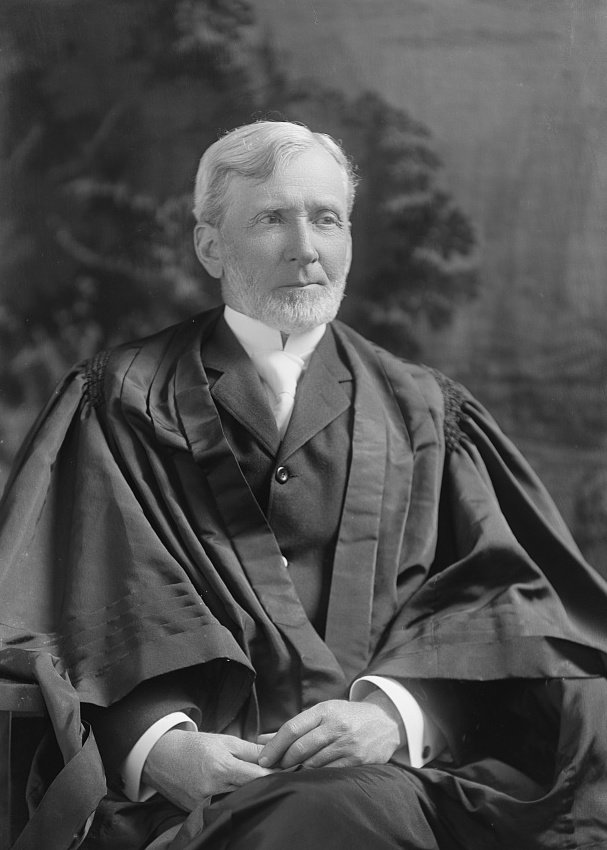

White

Brandeis

Day

Pitney

Van Devanter

Clarke

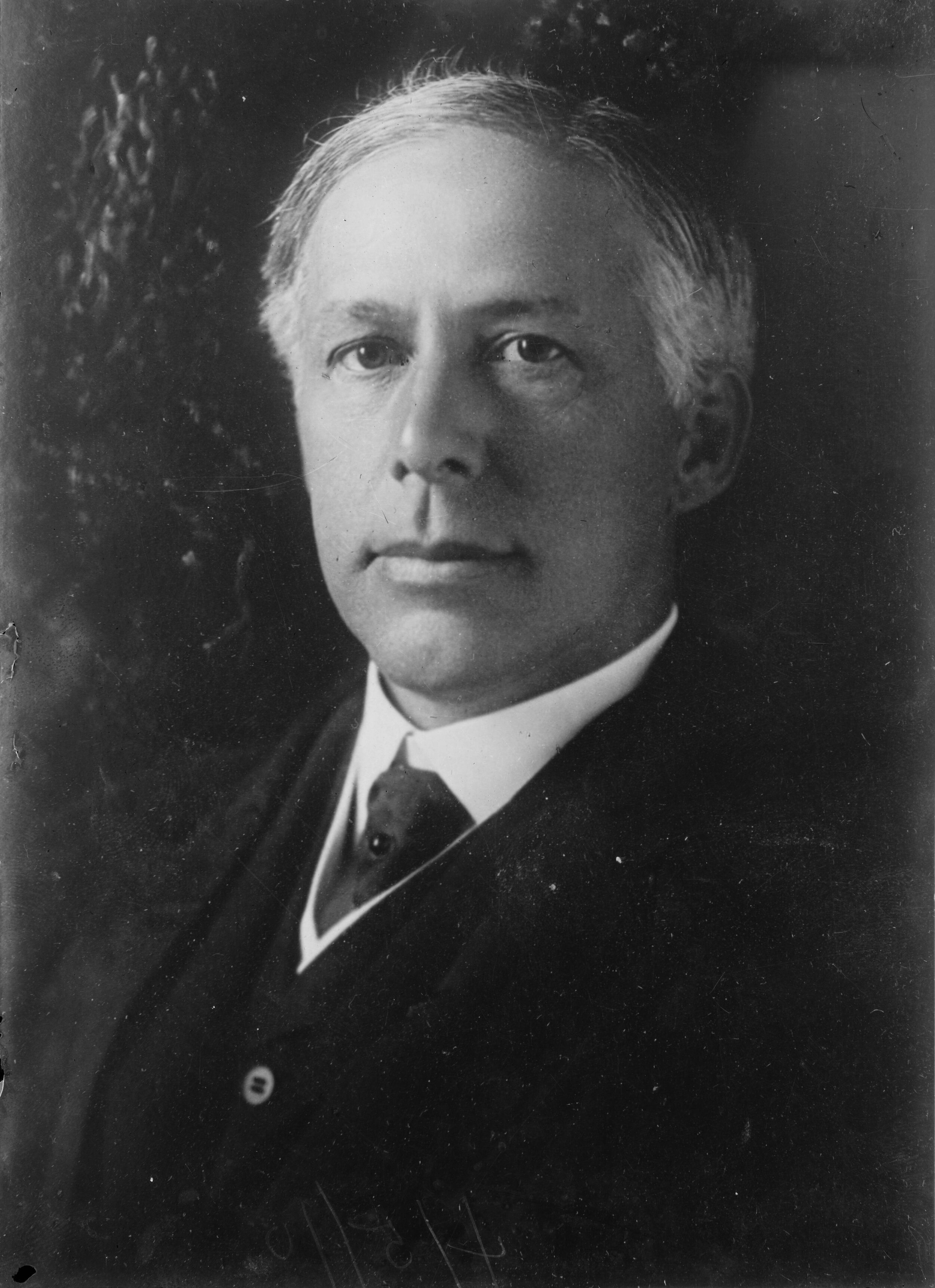

Holmes

McKenna

McReynolds

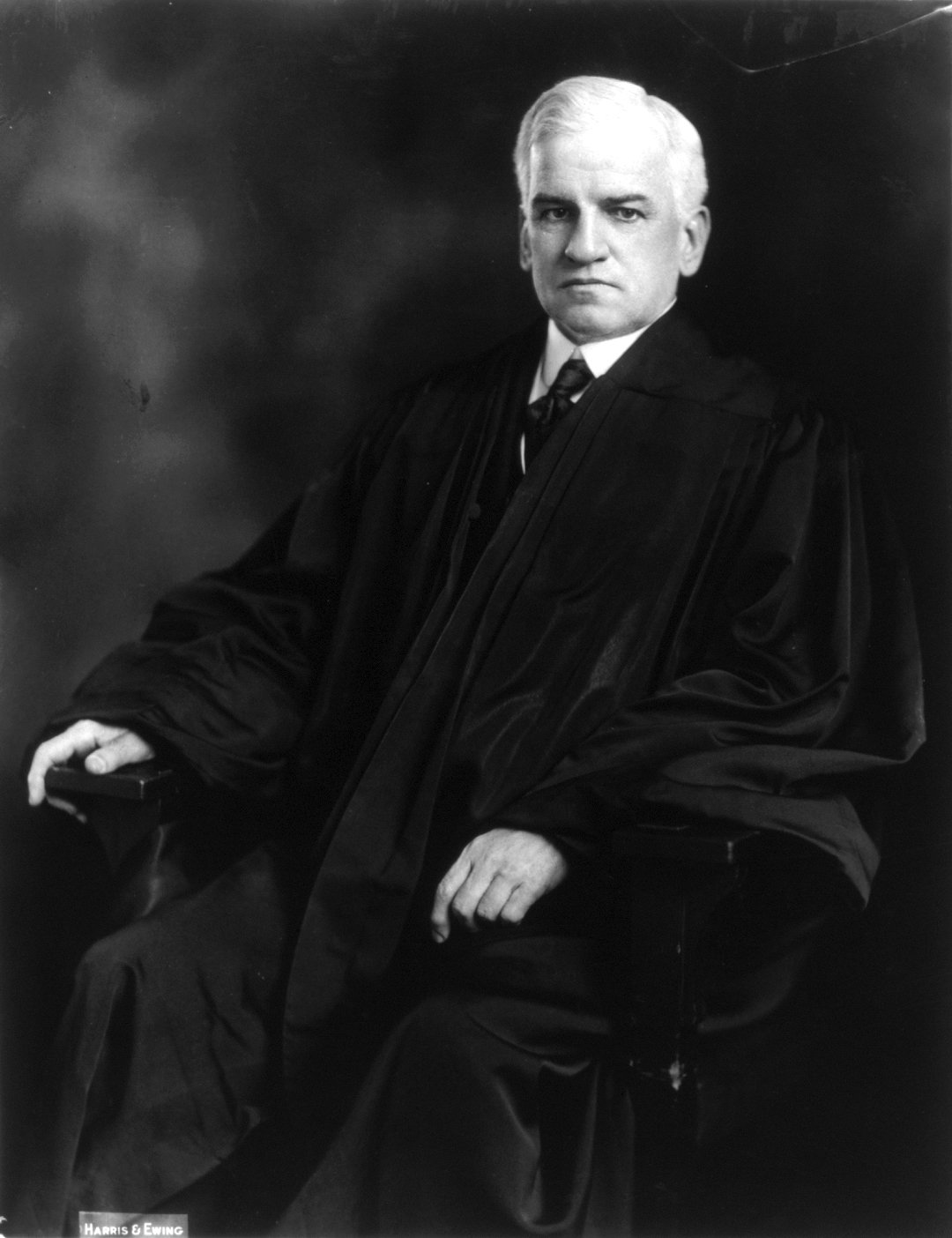

Opinion of the Court

Writing for a unanimous Court, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes established the clear and present danger test, a crucial standard for evaluating restrictions on free speech. Holmes wrote, “The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.” This standard essentially meant that speech could be restricted if it posed a direct and immediate threat to public safety or order. Holmes further elaborated on this principle, explaining that “[t]he most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.”

Holmes also distinguished between the intent and effect of Schenck's speech, arguing that while the pamphlets may not have directly incited violence, their potential to disrupt military recruitment and undermine the war effort constituted a clear and present danger. He noted, “[w]e admit that in many places and in ordinary times the defendants in saying all that was said in the circular would have been within their constitutional rights. . . but the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done.” Holmes acknowledged the importance of context in evaluating free speech claims and recognized that the government's power to restrict speech was broader during wartime, given the heightened need for national security and order.

While acknowledging the importance of protecting freedom of speech, Holmes stated that “[w]hen a nation is at war many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured.” Holmes ultimately concluded that free speech protections were not absolute and must be balanced with the government's duty to maintain order and security, particularly during wartime.

Cite this page

-

Schenck v. United States. (n.d.). Courtlib.us. https://www.courtlib.us/schenck-v-united-states.

-

"Schenck v. United States." Oyez, www.courtlib.us/schenck-v-united-states.

-

“Schenck v. United States.” Courtlib.us. https://www.courtlib.us/schenck-v-united-states.