McCulloch v. Maryland

Case Overview

CITATION

ARGUED ON

DECIDED ON

DECIDED BY

17 U.S. 316

Feb. 21 - Mar. 3, 1819

Mar. 6, 1819

Legal Issue

Does Congress have the authority to establish a national bank?

If Congress has such authority, can a state impose a tax on that bank?

Holding

Yes, Congress has the authority to create a national bank under the Necessary and Proper Clause of the Constitution.

No, states have no power, by taxation or otherwise, to retard, impede, burden, or in any manner control, the operations of the constitutional laws enacted by Congress to execute the powers vested in the general government.

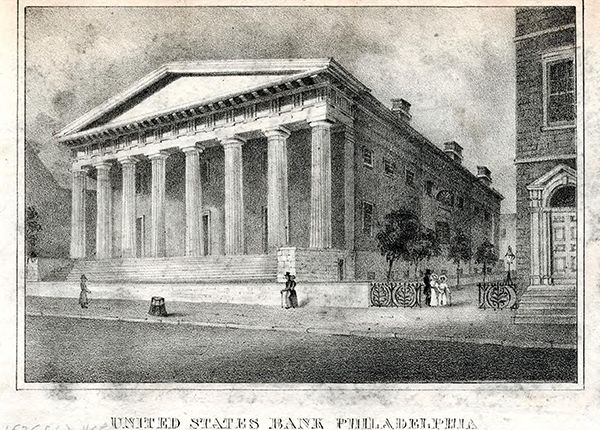

The building for the Second Bank of the United States in Philadelphia | Credit: Library Company of Philadelphia, World Digital Library

Background

In 1790, a debate erupted within the executive branch and Congress regarding the federal government’s authority to incorporate a national bank. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton championed the national bank as essential for the country’s financial stability. On the other hand, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Attorney General Edmund Randolph argued that the Constitution granted Congress no such power and that creating a bank would infringe upon state sovereignty. Nonetheless, Congress chartered the First Bank of the United States in 1791. Its charter expired in 1811, but the economic turmoil following the War of 1812 led Congress to charter the Second Bank of the United States in 1816, this time with the support of President James Madison, who had opposed the creation of the first bank.

The Second Bank, however, failed to resolve the country’s economic troubles and was widely blamed for making a severe depression worse. As the bank began calling in loans owed by the states, hostility toward it grew among state governments. In response, several states enacted legislation designed to hinder the bank’s operations. In 1818, the Maryland General Assembly passed a law imposing a tax on all banks or branches not chartered by the state legislature. The statute required such banks to either pay an annual tax of $15,000 or pay a stamp tax of 2% on all bank notes issued.

In May 1818, James William McCulloch, the cashier of the Baltimore branch of the Bank of the United States, issued bank notes to George Williams without paying the required tax or using the mandated stamped paper. John James, acting as an informer for the state, sued McCulloch and the bank in the County Court of Baltimore to recover the penalties prescribed by the law. The trial court ruled in favor of James and the State of Maryland. McCulloch appealed the decision to the Maryland Court of Appeals, the state’s highest court, but they affirmed the lower court’s judgment. McCulloch then appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court on a writ of error.

Summary

Unanimous decision for McCullough

McCullough

Maryland

Washington

Marshall

Livingston

Story

Johnson

Duvall

Todd

Opinion of the Court

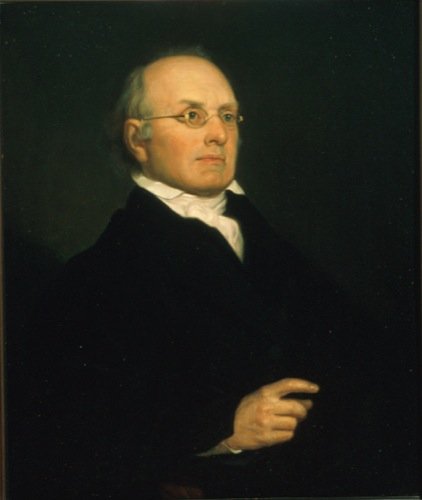

Writing for the Court, Chief Justice John Marshall first addressed the source of the Constitution’s authority. Marshall rejected the argument put forth by the Maryland that the Constitution is merely a compact among sovereign states that is derived from them and exercisable only in subordination to them. Marshall stated that while the Constitution was ratified by representatives of the individual states, it derives its authority directly from the people of the United States. Chase emphasized that the federal government’s authority emanates from the people, its powers are granted by them, and it acts directly upon them. Therefore, the Constitution and the laws made under it are supreme and binding to all states.

Marshall clarified that while the federal government is one of enumerated powers, the Constitution is not a legal code requiring every power to be expressly and minutely described. Unlike the Articles of Confederation, which excluded implied powers, the Constitution outlines great powers, such as the power to lay and collect taxes, borrow money, and regulate commerce, and implies the authority to carry out the means necessary for their execution. Marshall argued that a government entrusted with such vast powers must also be entrusted with ample means to implement and execute them. Marshall points out that the Tenth Amendment purposefully omits the word “expressly”, writing that “[t]he men who drew and adopted this amendment had experienced the embarrassments resulting from the insertion of this word in the articles of confederation, and probably omitted it, to avoid those embarrassments.”

Regarding Congress’ authority to incorporate a national bank under the Necessary and Proper Clause, Marshall rejected Maryland’s restrictive interpretation that the word “necessary” limits Congress to enact only legislation that is “most direct and simple”. Instead, Marshall argued that the word necessary is a term of degree and “frequently imports no more than that one thing is convenient, or useful, or essential to another. To employ the means necessary to an end, is generally understood as employing any means calculated to produce the end, and not as being confined to those single means, without which the end would be entirely unattainable.” Marshall contrasted this language with the phrase “absolutely necessary” found in Article I, Section 10 of the Constitution, arguing that the omission of the word “absolutely” in the Necessary and Proper Clause was intentional. Further, he observed that the clause is placed among the powers of Congress, not among the limitations, and purports to enlarge rather than diminish the Congress’ authority to pass laws.

Establishing a standard for constitutionality, Marshall wrote “[l]et the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the constitution, are constitutional.” Marshall emphasized the judiciary’s limited role in reviewing Congress’ actions, stating that “where the law is not prohibited, and is really calculated to effect any of the objects intrusted to the government, to undertake here to inquire into the decree of its necessity, would be to pass the line which circumscribes the judicial department, and to tread on legislative ground. Here, Marshall found that the incorporation of a bank is a convenient and appropriate means to execute Congress’ financial responsibilities under the Constitution and declined to review them past their constitutionality.

Marshall then addressed whether the Maryland could constitutionally tax the Bank of the United States. While Marshall acknowledged that the power of taxation is essential to the states and is generally concurrent with the federal government’s power of taxation, he noted that state power is subordinate to the Constitution. Marshall argued that the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause necessarily implies that the federal government must be immune from state control in the exercise of its powers. Marshall explained the important principles of supremacy, writing that they “are, 1st. That a power to create implies a power to preserve. 2d. That a power to destroy, if wielded by a different hand, is hostile to, and incompatible with these powers to create and to preserve. 3d. That where this repugnancy exists, that authority which is supreme must control, not yield to that over which it is supreme.” Marshall stated that “the power to tax involves the power to destroy” and explained that if the states were able to tax one instrument of the federal government, they could tax all other instruments (the mail, the mint, patent rights, etc.), which would effectively diminish the federal government and make it subject to the states.

Marshall distinguished between a state taxing its own constituents, where the elected legislature is held accountable by its responsibility to the people who pay the tax, and a state taxing the operations of the federal government. When a state taxes a part of the federal government, exerts power over institutions created by people over whom it has no control and who are not represented in its legislature. Marshall explained that the people of the United States did not design their government to be dependent on the states, and no state has the right to tax the means employed by the federal government to carry out its powers. Marshall ultimately concluded that the states have no power, either through taxation or other means, to retard, impede, burden, or control the operations of the constitutional laws enacted by congress... This is, we think, the unavoidable consequence of that supremacy which the constitution has declared.”