Marbury v. Madison

Case Overview

CITATION

ARGUED ON

DECIDED ON

DECIDED BY

5 U.S. 137

Feb. 11, 1803

Feb. 23, 1803

Legal Issues

Does Marbury have a right to the commission he demands?

If Marbury has a right, and that right has been violated, does U.S. law afford a remedy?

If U.S. law does afford a remedy, is it a mandamus issuing from the Supreme Court?

Holding

Yes, Marbury had a right to the commission because the appointment was legally complete once the President signed the document and the Secretary of State affixed the seal of the U.S.

Yes, because withholding the commission was a violation of a vested legal right, and civil liberty shields the right of an individual to claim protection under the law.

No, the Supreme Court lacks the authority to issue a mandamus because the legislative act granting the Court such authority was unconstitutional.

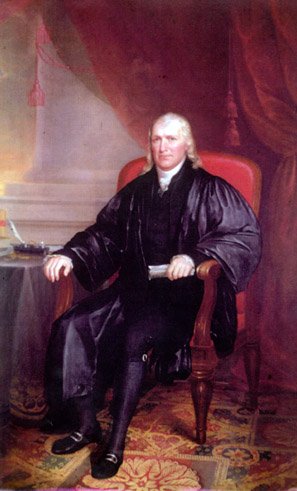

Portrait of William Marbury | Credit: Rembrandt Peale, Public Domain

Background

In the final days of John Adams’ presidency, Congress passed the Organic Act of the District of Columbia, authorizing the appointment of 42 justices of the peace to solidify Federalist influence in the judiciary. Two days before Thomas Jefferson was inaugurated, Adams nominated the judges. They were confirmed by the Senate the next day. The commissions were subsequently signed and sealed by Adams’ Secretary of State, but not all were delivered before Jefferson took office. Notably, Adams’ Secretary of State was John Marshall, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and author of the Court’s opinion in this case.

After being inaugurated, Jefferson instructed his Secretary of State, James Madison, to withhold the commissions that hadn’t yet been delivered. One of those belonged to William Marbury, who subsequently petitioned the Supreme Court under the Judiciary Act of 1789 for a writ of mandamus to compel Madison to deliver his commission.

Summary

Unanimous decision for Madison

Marbury

Madison

* Justices Cushing and Moore took no part in the consideration or decision of this case.

Paterson

Moore*

Marshall

Washington

Cushing*

Chase

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Chief Justice John Marshall first addressed whether Marbury had a right to the commission he was suing to be delivered. Marshall held that Marbury’s right to the office was complete upon the signing and sealing of the commission by the Secretary of State and that withholding the commission after that point is “not warranted by law, but violative of a vested legal right.”

On whether U.S. law provided Marbury with a remedy, Marshall asserted that the very essence of civil liberty requires that “the individual who considers himself injured has a right to resort to the laws of his country for a remedy.” In granting remedies, Marshall distinguished between “political agents” of the executive and and officials with “legislatively proscribed duties”. He explained that the discretionary acts of political agents are reviewable only through political channels, not the court. Conversely, officers with legislatively proscribed duties that individual rights depend on must be amenable to the laws of the country.

Regarding whether the Supreme Court even had the authority to issue the writ, Marshall held it did not. Marshall explained that the Judiciary Act of 1789, which granted the Court the power to issue the requested mandamus, conflicted with the Court’s original jurisdiction under Article III of the Constitution and was therefore unconstitutional. He explained that “[i]f it had been intended to leave it in the discretion of the legislature to apportion the judicial power between the supreme and inferior courts according to the will of that body, it would certainly have been useless to have proceeded further than to have defined the judicial power, and the tribunals in which it should be vested.” Such an intention would render “the distribution of jurisdiction made in the constitution, [] form without substance.”

Defending the Court’s ability to rule an act passed by Congress unconstitutional and therefore unenforceable, Marshall asserted that the U.S. Constitution is the “superior, paramount law” of the U.S. and that any legislative act repugnant to it is void. He stated that if “the courts are to regard the constitution; and the constitution is superior to any ordinary act of the legislature; the constitution, and not such ordinary act, must govern the case to which they both apply.” In this case, since the act was unconstitutional, the Court couldn’t grant Marbury a remedy allowed under it.

The Court’s decision to strike down the act as unconstitutional established the principle of judicial review, as Marshall declared, “[i]t is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases, must of necessity expound and interpret that rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the courts must decide on the operation of each.” Further, he asked, “[w]hy does a judge swear to discharge his duties agreeably to the constitution of the United States, if that constitution forms no rule for his government, if it is closed upon him and cannot be inspected by him?” Ultimately, the ruling affirmed the Supreme Court as a co-equal branch of the federal government and protected the Constitution’s supremacy in the country’s legal system.