Friends of the Earth, Inc. v.

Laidlaw Environmental Services

Case Overview

CITATION

ARGUED ON

DECIDED ON

DECIDED BY

528 U.S. 167

Oct. 12, 1999

Jan. 12, 2000

Legal Issues

Does Laidlaw Environmental Services’ voluntary cessation of their wrongful conduct render plaintiffs’ complaint moot?

Holding

No, the plaintiffs’ complaint is not moot because it was not absolutely clear that the wrongful conduct couldn’t reasonably be expected to recur.

Tyger River in South Carolina | Credit: Shelley Robbins

Background

Several environmental organizations, including Friends of the Earth, Inc., brought a citizen suit against Laidlaw Environmental Services under the Clean Water Act. Laidlaw operated a hazardous waste incinerator facility in Roebuck, South Carolina, and held a permit that limited its discharge of pollutants, including mercury, into the North Tyger River. Between 1987 and 1995, the facility repeatedly exceeded these discharge limits, so the plaintiffs sought declaratory and injunctive relief, as well as civil penalties.

The plaintiffs’ claim for standing rested on affidavits from local residents who stated they’d stopped using the North Tyger River for fishing, swimming, and other activities because of their concerns about the pollution. Laidlaw countered that the plaintiffs lacked standing because they hadn’t demonstrated any actual harm to the environment itself, only to their own subjective concerns.

Before the case was resolved, Laidlaw achieved substantial compliance with its permit and eventually shut down the Roebuck facility entirely. The company then argued that the case had become moot since the allegedly wrongful behavior had ceased. The District Court initially imposed a civil penalty, but the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals vacated the decision, ruling that the case became moot once Laidlaw came into compliance.

7 - 2 decision for Friends of the Earth

Friends of the Earth

Laidlaw

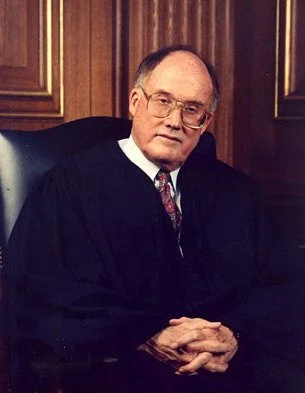

Stevens

Rehnquist

Kennedy

O’Connor

Souter

Alito

Breyer

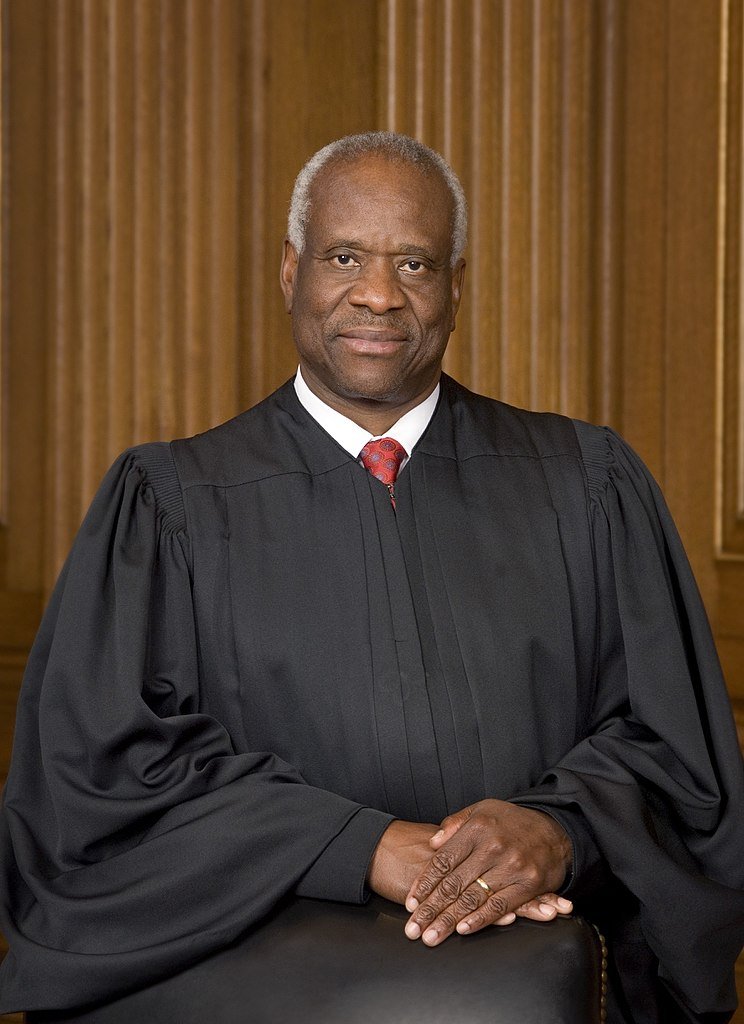

Thomas

Ginsburg

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg held that the plaintiffs had standing to sue and that the case hadn’t been rendered moot by the defendant’s voluntary compliance or facility closure. Ginsburg began by addressing the injury-in-fact requirement, distinguishing between injury to the environment and injury to the plaintiff. Ginsburg argued that the relevant inquiry for standing is whether the challenged conduct has caused the plaintiff a concrete injury, rather than whether it has caused a “discernible” injury to the environment. She found that the affidavits from local residents who stopped using the river for recreational and aesthetic purposes due to reasonable concerns about mercury pollution were sufficient to establish a personal injury that’s concrete and particularized.

Regarding the issue of mootness, Ginsburg explained that a defendant’s voluntary cessation of a challenged practice doesn’t automatically deprive a federal court of its power to determine the legality of that practice. Ginsburg established a “stringent” standard for mootness in cases of voluntary cessation, stating that a defendant must show that it’s “absolutely clear that the allegedly wrongful behavior could not reasonably be expected to recur.” Ginsburg noted that because Laidlaw still retained its permit to operate and had only closed the facility during the appeals process, the company hadn’t met this heavy burden.

Ultimately, the Court ruled that the civil penalties authorized by the Clean Water Act served a valid purpose of deterring future violations, which provided a form of redress for the plaintiffs' injuries. Ginsburg concluded that the case remained a live controversy because the threat of future pollution wasn't entirely eliminated. Consequently, the Court reversed the appellate decision and remanded the case for further proceedings.