Ford Motor Co. v. Montana’s

Eighth Judicial District Court, et al.

Key Principle

“Arise out of or relate to” Rule: a defendant’s contacts in the forum state may have either a causal connection (“arise out of”) or non-causal connection (“relates to”) to the plaintiff’s claims.

Case Overview

CITATION

ARGUED ON

DECIDED ON

DECIDED BY

592 U.S. 351

Oct. 7, 2020

Mar. 25, 2021

Legal Issue

Does the Due Process Clause require a strict causal “arises out of” connection or a non-causal “relates to” connection between the defendant’s contact in the forum state and the plaintiff’s claims to qualify for specific personal jurisdiction?

Holding

The Due Process Clause allows a court specific personal jurisdiction over a defendant if their contacts have either a causal connection (“arise out of”) or non-causal connection (“relates to”) to the plaintiff’s claims.

Ford’s HQ in Dearborn, Michigan | Credit: Dave Parker

Background

Ford is a global auto company incorporated in Delaware and headquartered in Michigan. Ford markets, sells, and services its products across the U.S. and globally. In the U.S. alone, Ford distributes over 2.5 million new cars, trucks, and SUVs to over 3,200 licensed dealerships on an annual basis. Ford encourages a resale market for its products, as almost all its dealerships buy and sell used Fords in addition to new models. Ford also engages in wide-ranging promotional activities and advertisements, such as their “Have you driven a Ford lately?” or “Built Ford Tough” campaigns. Ford also ensures that consumers can keep their vehicles running long past the date of sale by providing original parts to auto supply stores and repair shops across the country. This is also noted by their “Keep your Ford a Ford” ad campaign and their vast network of dealers around the country.

This case involved two plaintiffs who were victims of car accidents in 2015. Markkaya Gullett was driving her 1996 Ford Explorer near her home in Montana when the tread separated from a rear tire. The vehicle spun out, rolled into a ditch, and came to rest upside down. Gullett died as a result of the crash. A representative of Gullet’s estate sued Ford in Montana state court, alleging claims of a design defect, failure to warn, and negligence.. Adam Bandemer was a passenger in his friend’s 1994 Ford Crown Vic while traveling on a rural road in Minnesota to go ice-fishing. Bandemer’s friend rear-ended a snowplow and the car too landed in a ditch, but Bandemer’s air bag failed to deploy and he suffered serious brain damage as a result. Bandemer sued Ford in Minnesota state court, asserting products-liability, negligence, and breach-of-warranty claims.

Ford moved to dismiss both cases for lack of personal jurisdiction, claiming that the state courts only had jurisdiction if there was a causal connection between company’s conduct in the state and what gave rise to the plaintiff’s claims. They argued that such a causal connection only existed if the company had designed, manufactured, or sold the particular vehicle involved in the accident in the State. Neither plaintiff could prove that connection since Ford designed both the Explorer and Crown Victoria in Michigan, and manufactured them cars in Kentucky and Canada, respectively. Additionally, the Explorer was originally sold in Washington, and the Crown Vic in North Dakota. It was later resales and relocations by the cars’ owners that brought the vehicles to forum states.

The Supreme Courts of Montana and Minnesota both rejected Ford’s arguments, and SCOTUS granted certiorari.

Summary

Unanimous decision for Montana, et al.

Ford

Montana, et al.

Breyer

Kagan

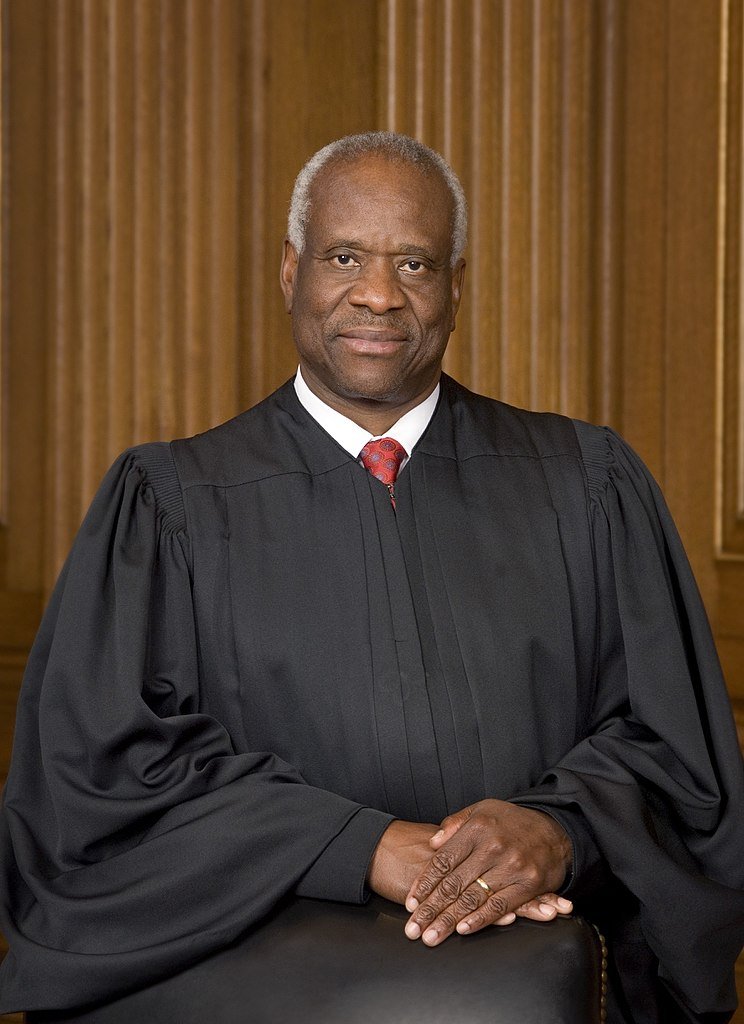

Thomas

Sotomayor

Gorsuch

Roberts

Alito

Kavanaugh

Barrett*

* Justice Barrett did not take part in the consideration or decision of the case.

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice Elena Kagan held that specific personal jurisdiction exists when [1] a defendant has “purposefully availed” itself of conducting activities in the forum state and [2] the plaintiff’s claims “arise out of or relate to” those contacts. Interpreting the “arise out of or relate to” element, the Court rejected the requirement of a strict causal link between the defendant’s contacts and the plaintiff’s claim and instead held that the “or” included in the phrase creates two independent pathways to jurisdiction. Justice Kagan explained that when a manufacturer systematically serves a market in the forum state and their product causes injury there, the state’s courts have the power to exercise jurisdiction regardless of where the specific product was designed, manufactured, or first sold, and stated two underlying principles behind this rule. First, Justice Kagan posited that the principle of fairness through reciprocity implies that when a company enjoys the benefits and protections of state law through extensive business operations, the state may hold it accountable for related misconduct and the company receives fair warning it will face jurisdiction where it systematically markets products. Second, Justice Kagan argued that the principle of interstate federalism implies that states with significant interests in a controversy being able to exercise jurisdiction over a dispute arising from or relating to their state rather than the case being heard in a jurisdiction with minimal connections.

In this case, Ford conceded it had purposefully availed itself of both Montana’s and Minnesota’s markets through their extensive operations. This included dozens of dealerships, targeted advertising of their vehicles, comprehensive repair services, and a vast network of replacement parts distribution. This left the question of whether their activity sufficiently “related to” the plaintiff’s claims arising from in-state product malfunctions. Justice Kagan found that since Ford had systematically served the markets for the very vehicle models that were alleged to have malfunctioned and injured the plaintiffs, such a connection existed. She explained that Ford’s advertising, accessible service, available parts, and active resale market potentially influenced residents’ purchasing decisions, and requiring proof of these causal chains would be impractical. On the principle of fairness, Justice Kagan argued that Ford enjoyed substantial benefits from operations in these states and had clear notice it could be subject to a lawsuit where its marketed products caused injury. Additionally, Montana and Minnesota had compelling interests in providing convenient forums for their citizens injured in such cases and enforcing safety regulations.