City of Cleburne, Texas v. Cleburne Living Center, Inc.

Case Overview

CITATION

ARGUED ON

DECIDED ON

DECIDED BY

473 U.S. 432

March 18, 1985

April 23, 1985

Legal Issue

Did the City of Cleburne’s denial of a permit for the Cleburne Living Center violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?

Holding

Yes, under a rational basis review, the City of Cleburne’s denial of a permit for the Cleburne Living Center violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Credit: The Texas Law Guide

Background

In July 1980, Jan Hannah purchased a building in Cleburne, Texas, intending to lease it to Cleburne Living Center, Inc. (CLC) to operate a group home for 13 adults with mild and moderate intellectual disabilities. Shortly after, the city informed CLC that it needed a special use permit because the city classified the home as a “hospital for the insane or feebleminded” under the zoning ordinance. After a public hearing, the City Council voted 3-1 to deny the permit application, citing concerns about neighborhood fears, the home’s location across from a junior high school, and its presence in a floodplain.

CLC and Advocacy, Inc. then filed suit in federal district court, alleging the ordinance violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The district court recognized that the only reason for the denial was that the residents would be intellectually disabled, the court upheld the ordinance under rational basis review as being tied to legitimate governmental interests. The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit reversed the district court, holding that intellectual disability constituted a “quasi-suspect classification” under an intermediate scrutiny test. The city appealed, and the Supreme Court granted certiorari.

Summary

Unanimous decision for Cleburne Living Center

Cleburne

Cleburne Living Center

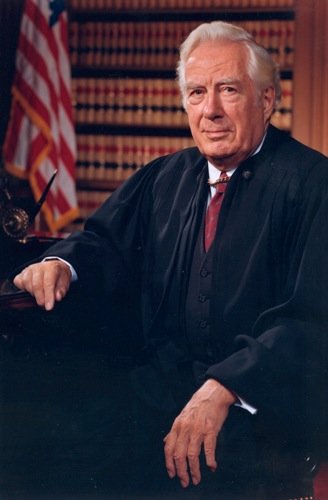

Burger

Powell

Blackmun

O’Connor

Marshall

Rehnquist

Brennan

Stevens

White

Opinion of the Court

Writing for the Court, Justice Byron White rejected the Fifth Circuit’s conclusion that the mentally disabled constitute a quasi-suspect class deserving heightened scrutiny. Justice White emphasized that intellectual disabilities are relevant to many areas of legislative concern, so legislatures must retain the flexibility to design laws and policies addressing their needs. He explained that intellectual disabilities vary widely in severity, and legislative measures for accommodations or supervision are often legitimate. Furthermore, Justice White pointed to action taken by federal and state governments in passing the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Education of the Handicapped Act, demonstrating political responsiveness to the needs of the disables and undermining any claim that they’re “politically powerless”. He explained that unlike race or alienage, classifications based on disability are not “so seldom relevant to the achievement of any legitimate state interest that laws grounded in such considerations are deemed to reflect prejudice.” On this line of reasoning, the Court determined that rational basis review was appropriate.

Even under a rational basis review, the Court struck down the ordinance as applied to CLC’s group home, finding no rational basis for treating the group home differently from other permitted uses in the R-3 zoning district, including fraternity houses, boarding houses, nursing homes, and apartment complexes. The Court contended that the proximity to the junior high school was invalid since many disabled students already attended the school, and concern over floods was irrelevant since other institutions allowed under the ordinance could also locate on flood plains. Regarding density, the Court noted that nothing in the ordinance prevented larger groups of non-disabled persons from living together in the same area. The Court found that mere negative attitudes or fears of neighbors “are not permissible bases” for government decision-making.

Ultimately, the Court concluded that the denial of the permit “appears to rest on an irrational prejudice against the mentally retarded” and therefore violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court affirmed the Fifth Circuit as to the ordinance’s invalidity as applied but vacated the ruling that intellectual disability constituted a quasi-suspect classification.

Concurring Judgment in Part and Dissent in Part by Justice Marshall

Justice Thurgood Marshall dissented in part, agreeing with the Court that the denial of the permit was unconstitutional, but objecting to the Court’s refusal to recognize the intellectually disabled as a class deserving of heightened scrutiny. Justice Marshall outlined the “lengthy and tragic history” of discrimination against the intellectually disabled, including forced institutionalization, eugenic sterilization laws, exclusion from schools, and disenfranchisement. He reasoned that such a history parallels the systemic mistreatment of racial minorities and women, and thus equal protection principles justified heightened scrutiny. Justice Marshall also dissented from the Court’s narrow remedy, which struck down the ordinance only as applied rather than on its face. He argued that leaving the ordinance intact forces future disabled applicants to “run the gauntlet” of discriminatory procedures and leaves them vulnerable to arbitrary denials.